System training. This is part of the curriculum when learning any new aircraft. Why is it important to talk about here?

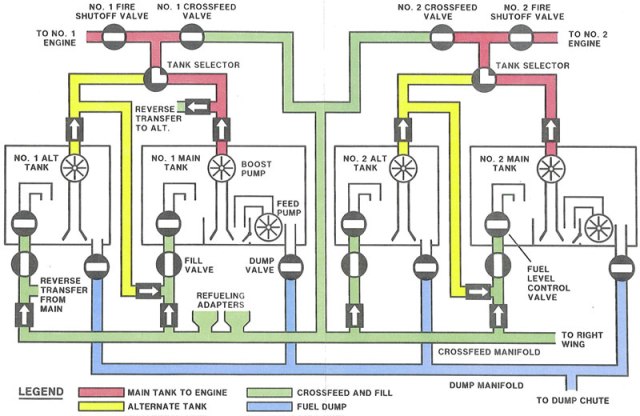

In recent years there has been a trend towards less and less system training. At one time we really needed to understand the systems. I can still draw the electrical system of a B-727, I still remember what bus powers the fuel pumps, dump values, what controls are powered by which hydraulic system, etc. This was standard for pilots. If a crossfeed valve failed on an classic B-747 all of us knew we could still move fuel via the dump manifold. I had similar knowledge of the DC-8 and other airplanes I had flown. As a testament to how well we learned these, I still remember most of the systems of those early airplanes after nearly 30 years!

Today I still have a fairly in depth understanding of the systems, but that is more due to my work outside of my flying job. It is not part of the curriculums anymore. What changed?

It can be argued that much of this was a result of automation, and that does explain some of it. Automated systems are able to act on their own to solve problems, so “why should someone know the details?” the logic goes. The truth is that the automation is only part of it. Engineers have been able to come up with simpler systems that accomplish what needs to be done for the fuel, electrical, hydraulic, pneumatic and flight control systems. In turn this allows for highly proceduralized steps to be written, which can then be put into checklists or automatic system responses. However, another factor has had an even greater impact on what is trained, and that is greatly improved component reliability.

Even 30 years ago it was not uncommon for a pilot to have experienced an engine failure during a career, or a failure in some other critical system. Today the probabilities of many of these types of failures is so low that a pilot has a good chance of flying an entire career with nary more than a fairly minor glitch. The lack of events (industry parlance for accidents or incidents) is then used as a basis for arguing that we should spend our limited training budgets on things that are statistically more likely to lead to an accident. We find those statistics by looking at the accident and incident trends. The industry uses methods that are somewhat limited in finding “root causes” of those accidents (there are serious flaws in this approach as the findings tend to be simplistic, at best) and these are used to build training scenarios. The training “footprint” is also used to teach pilots new technology that has been implemented, new procedures (such as RNP approaches), and the like. The result is a very full simulator period!

So, what’s the problem then? Well, the way the training is built, the aircraft manufacturers design and build the airplane, provide the aircraft and manual, and then the airlines and regulators are the ones that work to create the training programs. Well, really it is just the airlines, but the program needs to be approved. The manufacturers are rarely involved in what the airline actually teaches their pilots. This is a problem, as I have found that there is a gap between what the people who design airplanes and avionic systems believe pilots should know and what they are actually being taught.

The manufacturers all expect pilots to “fill the gaps” for those scenarios they could not foresee. Need evidence? A system fails and who is everyone blaming if the pilot does not prevent an accident or incident? I think we all know the answer here. There is more, however. Modern aircraft systems rely heavily on computers. These computers are “talking” to each other, and rely on information from other computers in the system to function properly. There is a term for this, “integrate modular avionics”. Now, these computers are extremely reliable, but if one of them gets bad information or faults, the problem can cascade across the other computers in the system in very unpredictable ways. Unpredictable and almost impossible to reproduce later, as exactly how they react depends on what data is being shared, what faults are present, the way it propagates through the system – even the lag due to the distance the information has to travel (length of the wires) can make a difference. Yes, that data is moving at the speed of light so we are talking about changes in the fractions of nanoseconds. From there, the systems not only fault in unpredictable ways, but also the “boxes” are likely to start sending alerts to the pilots of their problems, but these alerts are also going to present in ways that are impossible to predict. This is part of what the Air France 447 pilots needed to contend with!

So, suddenly, we have a very highly reliable system not just fail one aspect, as might have occurred in an airplane built 30 or more years ago, but instead take out all sorts of other systems, including very possibly degrading the flight control system itself! Now the pilot is left trying to sort out a lot of very confusing indications but the “scripts” that are normally relied upon, the checklists, procedures, just don’t apply anymore. Everything now depends on that system knowledge, all while flying an airplane that possibly no longer handles like anything they have ever experienced (training for degraded flight control laws in FBW aircraft is often very limited as well).

We have seen pilots who had “above and beyond” knowledge do a good job of handling unusual scenarios. “Sully” Sullenberger did it when he started the APU out of sequence, restoring normal law to the flight controls. The pilot of Qantas 72, Kevin Sullivan (coincidentally, also nicknamed “Sully”) used his superior knowledge to handle what could have been a catastrophic flight control failure. In a May 2017 article in The Sydney Morning Herald on the event he said something that should resonate with most pilots:

“Even though these planes are super-safe and they’re so easy to fly, when they fail they are presenting pilots with situations that are confusing and potentially outside the realms to recover” he says. “For pilots – to me – it’s leading you down the garden path to say, ‘You don’t need to know how to fly anymore.’ You just sit there – until things go wrong.”

Both of the “Sully”s had something that is not trained anymore. They “grew up” in a time prior to the highly reliable components, before RVSM rules made hand-flying at altitude virtually illegal, when pilots still needed to learn their systems. They carried that to the day when they needed that information and those skills. Notice this is not about just “hand-flying more”. Hand-flying a normal airplane is fun and good, but is not going to equip you to handle a real degraded flight control state. Plus, most hand-flying is done at lower altitude with limited configuration changes, not a great preparation for a degraded airplane in the upper flight levels.

While it is a great ploy for the marketing departments to state that pilots can get by with minimal training due to the reliability of the systems an the automation, the reality is that they can get by with it until the day they can’t, and we have no idea when that day might come. The engineers tend to have a different take then the folks that are trying to sell airplanes, as previously stated. They expect pilots to “fill the gaps”.

There are also times when more system knowledge can make a big difference even with no failures. One that comes immediately to mind are the automated radar systems. While these can improve the situation if a pilot had minimal training, the fact is that they still leave significant gaps due to the relative simplicity of the models they use to scan for weather. They can also lead pilots to think that there is not weather ahead when in reality the algorithm is just not depicting the weather due to a difference in the vertical liquid profile of the particular storm in that part of the world. A pilot with more knowledge on meteorology as well as radar functioning can fill those gaps.

A pilot with more knowledge can also prevent other problems, such as a delay due to just misunderstanding what the system is doing. Granted there are some that might “overthink” in these situations, but this, too, can be rectified.

Pilots remain the most important safety feature on the airplane. System knowledge can be hard to find these days. What really needs to happen is when designing training programs the airlines should be required by regulation to consult with the manufacturers to ensure that pilots are being taught what the manufacturer thinks is important (regarding systems, handling qualities and pertinent aerodynamics, what pilots should have as skill sets to fly the airplanes after various faults, but not operations). That is, the men and women that actually are involved in the design. In the meantime, though, we pilots are on our own.

I do not anticipate the airlines voluntarily increasing the training footprint (although there may be ways to teach what needs to be taught without a significant increase), so it is up to us to go out and learn what we need to on our own. As an example, while Boeing stopped publishing, there are still many issues of its magazine, (Boeing Aero) and Airbus has two good in-house magazines (Airbus FAST and Airbus Safety First) that should be read (even if you don’t fly one of their products), and there are other sources as well,such as Skybrary. Google what you want to learn, you might be surprised. I realize it is frustrating to have to go out and learn things not provided by your company, but the person you might be saving is yourself!

=====================================================

You must be logged in to post a comment.